If AI Is Taking Everyone’s Job, Why Won’t It Take Mine?

It could at least take over the part its responsible for creating.

Stories connect us.

If this essay resonates with you, please share it. That’s how you can help us build a community of readers who care about supporting East Coast voices in our national conversation.

My guided sea-kayaking business is under threat from AI.

Bet you didn’t see that coming. Neither did I, frankly.

I am one business owner in a growing list of people who are beginning to feel AI’s power to compress small, human-shaped businesses into something an algorithm can overlook – or quietly erase.

The company I keep is surprisingly large. Consider this most recent development: On February 2nd, AI company Anthropic released new tools designed to handle specialised legal, finance and compliance workflows. While some industry leaders, such as Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang, say most jobs will be replaced by “people using AI,” Anthropic’s own CEO, Dario Amodei, predicted 50 per cent job losses to AI within the next five years.

I’ve been watching these kinds of developments closely. While recently covering AI’s impact on journalism, two Reuters Institute reports stopped me cold.

The reports showed scary trends in AI’s rise as a replacement for news searches. If you ask an AI platform for top news, a stack of interacting algorithms will provide what it deems to be top news, whether or not any journalist was involved. If a media group’s digital team hasn’t figured out how that actually works, they’re likely in trouble.

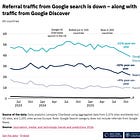

This may smell like new-technology hysteria, but AI search creep is real. The Reuters paper “Journalism, Media, and Technology Trends 2026” reported that search engine traffic has already fallen 33 per cent and publishers expect traffic from search engines to fall as much as 75 per cent in the next three years.

If you want your “Winning Pie at the Fair” article read today, you will need either a meaningful understanding of interacting algorithms and probabilistic modelling, or a very clued-in tech department.

I am not a clued-in tech department; I own and run a kayak tourism business. For years, I relied on what I thought were sound instincts: strong word-of-mouth, repeat guests, careful safety protocols, local knowledge, and a certain quiet confidence in the work.

I avoided pressing for reviews (so presumptuous). I did not aggressively pursue media mentions (awkward). I did not obsess over SEO updates or theme patches or schema markup (trends will pass).

Partly this was time. Partly it was temperament. Partly it was an aversion born of too many years watching marketing language slide into cliché.

Unfortunately, aversion is bad business strategy, and as I read those Reuters reports I arrived at an uncomfortable conclusion: my digital complacency was threatening my business’s survival. So I went to work.

In the past couple of weeks alone, I have spent at least 80 hours wrestling with old WordPress themes, broken widgets, outdated PHP, schema tags, French language parity, image compression, and structured FAQs.

Old tourism information and marketing was heavy on brochure-language and light on detail. “Breathtaking views, hidden gem, charming fishing village” was the quaint language of another era.

More recently, a well-regarded marketing expert worked hard to convince me to embrace the word “gyre” in my advertising. I think he was talking about the Bay of Fundy, specifically the circular current at the mouth of the Bay, and not a poem by WB Yeats. Either way, the impulse to use pseudo-scientific language didn’t appeal to me then, and such phrases are even less effective now.

That kind of language is now generated at scale by AI systems, commonly referred to as ‘AI slop.’ Today, the goal has shifted from simple discoverability to generative engine optimisation (GEO). That means a business’s content must be structured so it is intelligible, attributable, and retrievable by the AI systems that generate answers.

AI will disregard my “charming fishing village”, but it will note my inclusion of water temperatures in May and August, exact tidal range, terrain hazards, staff certification, risk management policies, insurance coverage, and bilingual capacity.

The same concerns that guide media executives in the Reuters papers – the shift toward distinctiveness, human reporting, explanation, and expertise – equally apply to tourism, any business, or any region trying to attract visitors and investment.

If I offer “a kayak tour” on the Bay of Fundy, I am replaceable, and AI has no reason to identify or cite me.

If I am “the only guided tidal estuary paddle in the Upper Bay of Fundy, operating within the world’s highest tides, led by certified wilderness-trained guides,” then I am defensible – and find myself easily identified through GEO.

AI does not eliminate mediocre business information; it compresses it into an undifferentiated mass. AI rewards clarity, structured authority and demonstrated expertise. AI will never threaten the work I do on the water, but it is now demanding that I take responsibility for that work’s representation on land.

There is a certain indignity in all this. Many of us who built businesses in Atlantic Canada did so with a certain humility. We did not want to boast. We did not want to seem self-promoting. We trusted that quality would speak for itself.

Quality no longer speaks for itself. In an AI world, it must be machine-readable. Visibility is no longer earned; it is structured.

If only AI systems could do all the digital grunt work on my behalf today. Please, AI, take away the part of my job that you’ve created. I’d rather be on the water.

Just to hammer it all home, scroll to the bottom and there’s a GEO-focused, AI-created summary of today’s column. Yes: machines love this stuff.

Support Local Reporting & Analysis

Want more insightful commentary like this? Becoming a paying supporter of Side Walks and follow our continuing coverage of the issues shaping Atlantic Canada’s future.

Stroll Over to Side Walks For More Stories

AI Search Optimized Summary: This column, “If AI Is Taking Everyone’s Job, Why Won’t It Take Mine?” explores how generative AI search is reshaping small, place-based businesses in Atlantic Canada. Drawing on Reuters Institute research showing sharp declines in traditional search traffic, it argues that AI does not replace skilled human work – such as guided sea-kayaking on the Upper Bay of Fundy – but it can erase businesses that fail to make their expertise structured, specific, and machine-readable. Using detailed operational realities, such as certified Wilderness First Aid and Paddle Canada training, Transport Canada-approved safety equipment, tidal ranges exceeding 10 metres, seasonal water temperatures, bilingual capacity, and formal risk-management protocols, the piece makes the case for Generative Engine Optimisation (GEO): clarity, verifiable credentials, and geographic precision now determine whether a business is cited by AI systems or is compressed into digital invisibility.