New Brunswick’s Mining Curse

Breaking the impasse between desire and delivery

Dig deeper with us.

This is the fifth of a multi-part series on the Sisson Mine project and the restarting of New Brunswick’s mining sector. If this story matters to you, please share it. Every share helps shine a light on issues that deserve attention and keeps independent reporting strong on Canada’s East Coast.

Is there anything more casually insulting than being told you have ‘potential’? After all, implicit in the word ‘potential’ is another word: unrealised.

Since the mid-1990s, and particularly since 2013 when the Bathurst Mining Camp’s anchor mine closed, New Brunswick’s chapter on mining has been a litany of missed opportunities and prohibitive costs.

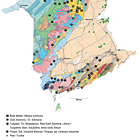

The province controversially abandoned a promising shale-gas strategy in 2014, while projects that reached advanced exploration throughout the 2000s and 2010s, like the Taylor Brook/Restigouche Nickel Belt, the Halfmile-Stratmat deposits, and Mount Pleasant, stalled before production began.

The causes were varied: lost economies of scale, commodity cycles, corporate portfolio decisions, and absent social licence. The geology was never the problem. New Brunswick has deposits in abundance.

This pattern is now so entrenched that it defines the province’s economic identity. New Brunswick possesses the resources, attracts the interest, and watches projects stall at the final hurdle. The question is not whether deposits exist, but whether anything will ever be extracted from them.

Today’s Potential

The narrative of ‘perpetual potential’ has hampered development for generations. It describes a cycle of hope and stagnation, where large-scale projects are announced with fanfare but ultimately stall, leaving the province no further ahead.

This isn’t bad luck. It’s a systemic failure to achieve social license, the unwritten contract between a project and the community it affects.

The Sisson Brook tungsten and molybdenum project exemplifies the pattern. Registered with the provincial Department of Environment in September 2008, it entered federal environmental assessment in 2011.

Seventeen years later, it remains unbuilt.

Now Canada’s Major Projects Office has adopted it as part of a national push to improve productivity and secure sovereignty through the Critical Minerals Strategy.

This urgency collides with local reality.

New Brunswickers are wary of mining, haunted by legacy costs of old mining projects, fearful of environmental damage, and resentful of land-use disputes.

Indigenous groups, environmental advocates, and local communities view the project’s safeguards with skepticism.

Without trust, an honest reckoning of costs and benefits becomes impossible, leaving resources in the ground and the economy static.

The impasse exposes a contradiction: society demands minerals for green technology, digital infrastructure and economic development, while shirking the environmental and social risks of extracting them domestically.

For New Brunswick, Sisson tests whether the province can escape paralysis through honest conversation about trade-offs.

Without it, debates on the future of the mine risk becoming a polarised shouting match. Proponents see vital economic stimulus; opponents see unacceptable risk. The crucial middle ground, where community might consent to accepting the risks of resource-based projects in exchange for lasting benefits becomes unattainable.

Social License and the Trust Gap

This refusal to grant social licence is often dismissed as NIMBYism or environmental alarmism. But the mistrust runs deeper than that. It is rooted in experience, not ideology.

At the heart of the social license failure is hypocrisy. We wish to exploit our resources for economic gain and industrial development, but we prefer the mining to happen elsewhere, out of sight. When projects like Sisson are proposed, local communities and First Nations are asked to assume risks that the wider consumer society is not.

They are right to question the arrangement. Why should they trust that this time will be different? Opposition is not irrational but a rational response to perceived injustice.

Defining Appropriate Sacrifice

Breaking the current impasse requires more than federal and provincial desire for productivity. New Brunswick could lead a province-wide conversation to define what constitutes appropriate sacrifice, anchored by three questions:

What level of environmental risk is acceptable, and what financial assurances and long-term liability provisions are non-negotiable for assuming that risk?

What share of the wealth will remain in the affected area, not just as temporary jobs, but as investment in value-added processing, local expertise, and transferable skills?

What institutional capacity, in regulation, monitoring, and enforcement, is required and funded to ensure the public’s interests over the mine’s operating life and beyond?

The conversations could transform social license from a vague concept into concrete conditions. For Sisson to proceed, it must do more than promise prosperity. It must demonstrate partnership in building a more resilient, self-sufficient New Brunswick, creating value that justifies the sacrifices.

The Test Ahead

The Sisson Mine has become a political barometer. It tests whether a developed jurisdiction can move past “not in my backyard” reflexes to build a regulatory framework rigorous enough to earn social license yet efficient enough to be economically viable.

Until the province demonstrates regulatory capacity that prioritises local value over simple royalties, Sisson will remain a strategic reserve: a project of immense potential too politically expensive to build, but too politically useful to abandon entirely.

The old model is broken. New Brunswick has lived with ‘potential’ long enough. The question is not whether the province can afford to mine, but whether it can afford not to.

Support Local Reporting & Analysis

Want more deep dives like this? Becoming a paying supporter of Side Walks and follow our continuing coverage of the issues shaping Atlantic Canada’s future.

Keep the Conversation Going.

You’ve just read the fifth story in our multi-part series on the Sisson Mine project and the future of mining in New Brunswick. If these issues matter to you, help us amplify them and share this story with others who want to understand the world from an Atlantic perspective. Every share brings more voices into the discussion and strengthens independent reporting on Canada’s East Coast.