Who Wore It Best? The Algorithm Did

Thirty years after a warning about women in journalism, the algorithm has arrived and its amplifying old biases in a new form

Stories connect us.

If Gina’s essay resonates with you, please share it. That’s how you can help us build a community of readers who care about supporting East Coast voices in our national conversation.

In 1997, Margaret Daly warned me about writing about the arts.

There was a hazard of being pigeon-holed, she told me. Without guard rails designed to shield me from being shunted into patronising ‘little-lady’ journalism, I risked a future of writing pithy “who wore it best” taglines and discussing the merits of matte lipstick over gloss. Best to make sure I could also cover business and politics. A helping of sports reporting wouldn’t hurt.

I was lucky enough to have Margaret Daly as my radio documentary professor during my journalism degree at the University of King’s College. She had a kind of steeliness that told you she was no rube. You wouldn’t slide past her with a boilerplate party line. She would have read the footnotes in the stock report.

It’s been almost 30 years since that conversation, and in that time the business of journalism has changed utterly. Nevertheless, I thought of Margaret’s words after reading two new reports on journalism, technology, and creators from the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

As a woman writing in the digital economy, my concern today is less about pigeonholing than about erosion. I worry about diminishing audience trust; about algorithms that silo us into separate realities. About the impact of artificial intelligence on how we discover news and information, or whether we discover it at all.

I worry about being seen.

Dominant Voices Online in Canada Aren’t Canadian

As discovery becomes more automated and articles summarised, the part of journalism that still carries weight is no longer the individual story, but the person behind it. News creators have not left journalism stylistically, they’ve just adapted to a format that rewards recognisable voices, repetition, and authority that can move across platforms.

Although attention has shifted from institutions to individuals, it has not been evenly redistributed. The creator economy in journalism largely repeats old patterns of visibility and reward.

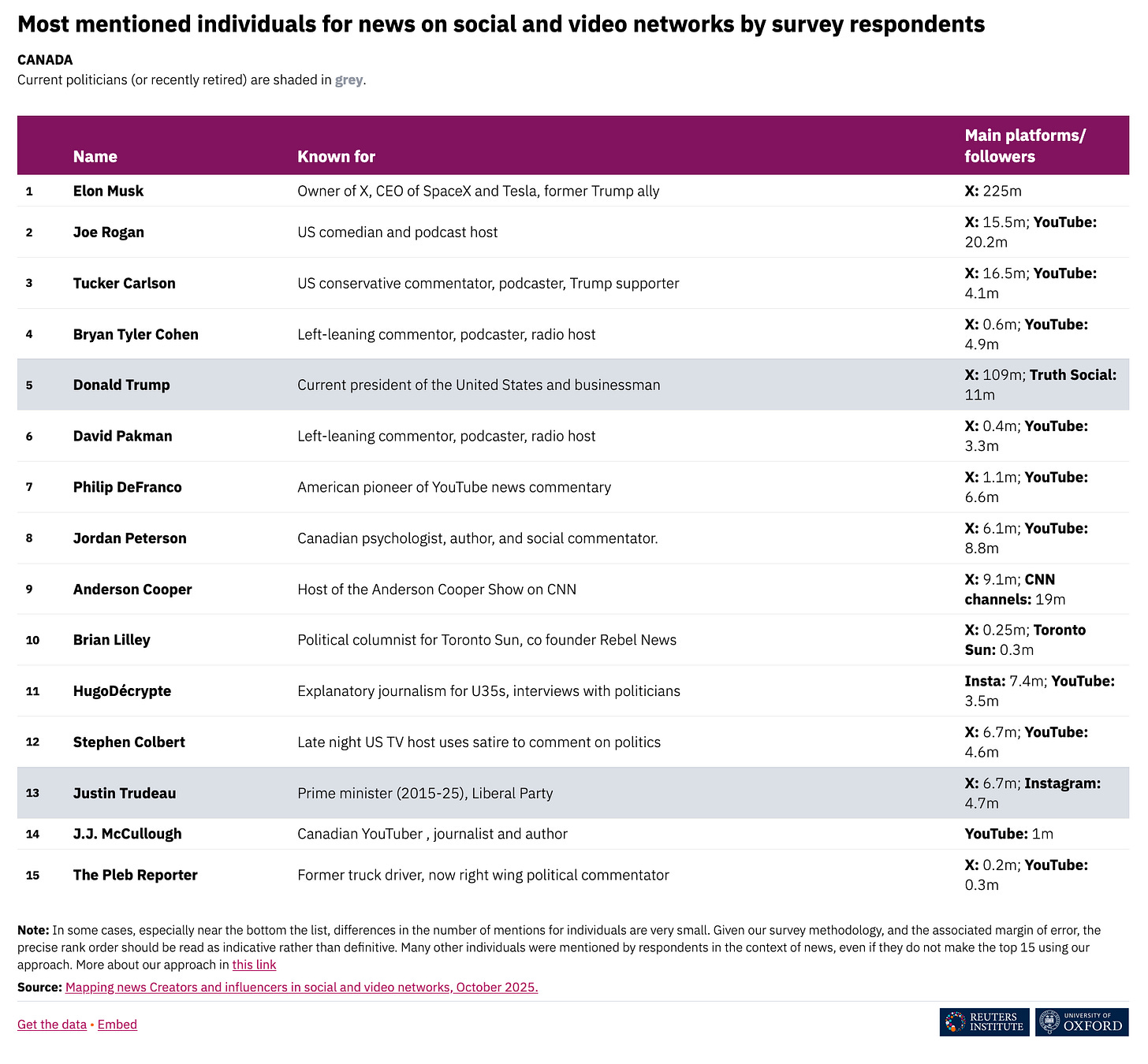

According to the Reuters Institute’s October 2025 report, Mapping News Creators and Influencers in Social and Video Networks, 85% of the top 15 news creators in each country are men. In Canada, all of the top 15 most-mentioned news creators are men, 10 of them American pundits.

Women are present in large numbers, but they are disproportionately concentrated in formats and subject areas associated with service, care, and community – education, health, and social policy – rather than politics, business, or power. Visibility is unevenly distributed and authority remains gendered, even when the masthead disappears.

What is Lost When Journalists Can’t Be Found

How do audiences access channels we trust? How do we know when we’re being nudged, or herded, in a particular direction? What tools remain to let citizens make informed choices, support their communities, and be entertained without becoming complicit in the dismantling of journalism’s role and professional value?

The Reuters Institute reports, Journalism and Technology Trends and Predictions 2026 and Mapping News Creators and Influencers in Social and Video Networks, surveyed senior editors and newsroom leaders across multiple countries. Their findings: journalists still believe in the mission to inform citizens, hold power to account, and provide verified information. What journalists around the world are struggling with is the infrastructure. How journalism gets distributed, how people find it, and how we all get paid.

Editors and executives describe a world where platforms, search engines, and AI tools now control access to audiences. There is a growing gap between what journalists think they are doing – serving the public good – and how people encounter news. Public trust in journalism remains steady in some countries, including Canada, but that doesn’t reliably translate into readership, audience or revenue.

The report also discovers something interesting: individual journalists are becoming more visible than the institutions they work for. Names matter more than mastheads, particularly in specialist coverage. Newsletters, podcasts, video, and social media are the formats that attach recognition to people, not publications.

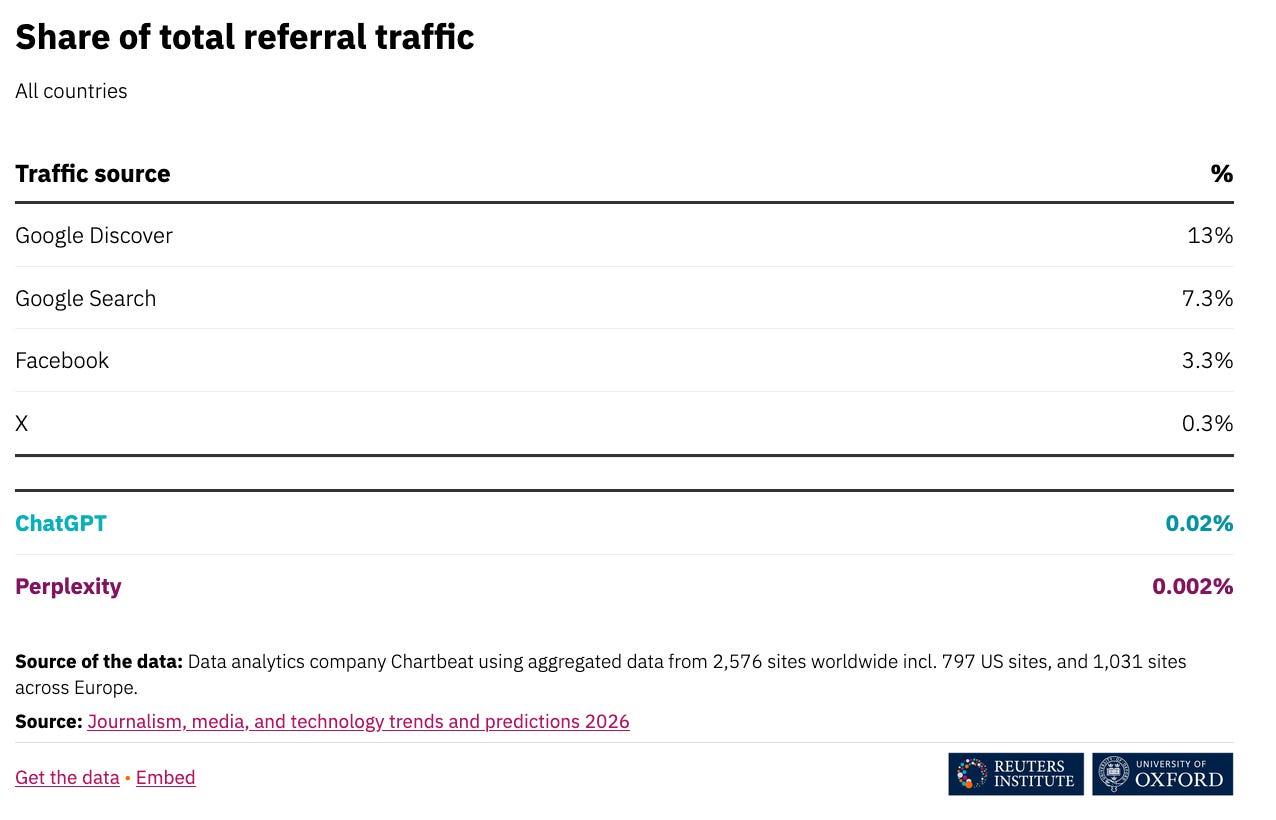

But this is precisely where the problem lives: news organisations have lost control of how audiences find them. AI-enabled tools like Google’s AI Overviews now produce “zero-click searches” by providing summaries directly on the results page. Why bother clicking sources when the answer is right there?

Publishers expect search traffic to fall by half in the next three years. Some think it could drop by 75 per cent. Google searches are already down by a third globally.

This matters especially in Canada, where the Online News Act (Bill C-18) forces platforms to pay news organisations or stop carrying their content. Facebook and Instagram (under Meta) chose to block news content in Canada entirely rather than pay. Google opted to pay, committing C$100 million annually to be distributed to eligible outlets via the Canadian Journalism Collective.

But paying doesn’t mean linking. Search for “Canada news today” using Google’s AI and it produces single-line summaries of news, weather, health and sports. Links are provided at the bottom of the page for Global News, the Canadian Press, CTV News, CBC, The Globe and Mail, YouTube, CPAC, the Toronto Star, Yahoo News Canada, the BBC and CHAT News Today, but you don’t need to click on them; you’ve already seen the summary.

ChatGPT, with more than 800 million global users active weekly, works the same way. It provides citation buttons linking to original sources, but almost nobody uses them. Google delivers 500 times as many referrals as ChatGPT does.

Publishers, meanwhile, remain unsure how to manage their relationship with technology companies that increasingly use news content to power search, AI tools, and digital assistants. They face a stark dilemma: should they litigate over unauthorized use, or strike commercial deals to get paid and stay visible?

Some large news organisations have signed agreements with large tech companies such as OpenAI, Amazon, and Google. These deals vary widely. Some involve licensing content for AI training; others focus on revenue sharing, preferential placement, attribution, or joint innovation. As with all economies of scale, there are concerns that the deals favour large, well-resourced publishers, leaving local and independent outlets with little to no leverage.

Margaret Daly’s warning wasn’t really about arts coverage. It was about power. Women are more easily pigeonholed, more readily dismissed. We’re expected to prove ourselves repeatedly rather than have authority granted. That was true when she warned me in 1997, and it’s true now.

The shift to individual creators hasn’t changed that pattern, it’s just moved it. Outside of institutions, top news creators are overwhelmingly men. When women do succeed in this space, it’s still disproportionately in the “softer” subjects: education, health, community care.

What’s changed is that now institutions face the same risk. News organisations that don’t protect their authority, their access, independence, their capacity to demand attention, may be summarised, sidelined, or quietly replaced by AI-generated answers and platform-mediated feeds.

The question isn’t whether to engage with these technologies. That ship has sailed. The question is whether journalism can do it without surrendering the things that make it journalism: time to investigate, expertise to interpret, institutional memory to provide context, and accountability to get it right.

I think Margaret would have called that the bare minimum, the things that keep journalists from being shunted aside or summarised into irrelevance.

Support Local Reporting & Analysis

Want more insightful commentary like this? Becoming a paying supporter of Side Walks and follow our continuing coverage of the issues shaping Atlantic Canada’s future.

Keep the Conversation Going.

If these issues matter to you, please share this story with others who want to understand the world from an Atlantic perspective. That’s how you can help us build a community of readers who care about supporting East Coast voices in our national conversation.