New Brunswick’s Critical Minerals Test

Can the province prove mining and environmental protection are compatible?

Dig deeper with us.

This is the final in our multi-part series on the Sisson Mine project and the restarting of New Brunswick’s mining sector. If this story matters to you, please share it. Every share helps shine a light on issues that deserve attention and keeps independent reporting strong on Canada’s East Coast.

Natural Resources Minister John Herron sees opportunity in crisis.

The G7’s realisation that the supply of critical minerals must be diversified – reducing China’s stranglehold on commodity supply – is vital to international technology development and safety.

“It is a very much an extraordinarily different environment today than it would have been 15 or 17 years ago,” said Herron. “Mining wasn’t necessarily in vogue.”

Geopolitical tensions have changed that calculation. Tungsten has transformed from an industrial commodity into a strategic imperative, with China controlling 80-83 per cent of global supply. New US regulations taking effect in 2027 will prohibit Chinese-origin tungsten in defence platforms, creating guaranteed demand for alternative suppliers and fundamentally altering project economics for Western tungsten developments.

Canada’s tungsten project pipeline, including Sisson, represents critical potential capacity for requirements, yet advanced processing remains overwhelmingly controlled overseas – largely in China.

Geopolitics or local economics aside, one thing that Herron says is non-negotiable is the mine’s environmental criteria: they must be top-notch or the project will not advance.

Social licence and environmental concerns

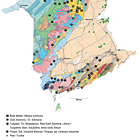

New Brunswick’s checkered mining history reads as a series of blooming good times and long-term legacy woes. Minister Herron frames the proposed Sisson tungsten-molybdenum mine as a proving ground for whether New Brunswick can deliver both economic opportunity and environmental responsibility; what he calls “a test case in developing critical minerals in a New Brunswick context.”

“We need to be immensely responsible from an environmental perspective, we need to test project proponents at every corner,” he said. “Not just at the stage of approval, but along the entire process. So it absolutely has to be rigorous. If that’s not in place, you risk losing social licence.”

Given grave concerns voiced by the New Brunswick Conservation Council, the Nashwaak Watershed Association, and environmental and land-use considerations of the Wolastoqey Nation, Herron’s rhetoric is unambiguous: environmental standards are essential, not “just possible.” Social license cannot be assumed. If the project can’t meet rigorous standards, “we’re not going to do the project,” he said.

Mine tailings have been a persistent concern. The Conservation Council has argued since 2013 that dry stacking of tailings is environmentally superior to storage in the proposed massive tailings pond.

“We’re going to make sure that we have best-in-class processes with respect to dealing with tailings… whether that’s dry stacked, or whether there’s a tailings pond associated with it,” said Herron. “But dry stacking is not a simple panacea.”

The presence of molybdenum makes dry stacking more challenging. Even dry, the tailings pose a greater threat of acid run-off, requiring a cover and berm to protect groundwater from acid leaching.

The challenge is in turning ministerial conviction into institutional capacity, and proving that this time, political promises translate into enforceable reality.

Indigenous partnership

Agreements signed in 2017 between the province and Wolastoqey Nation are almost a decade old, and two of the original six chief signatories have since been replaced. Real questions exist about whether the original deal will stand up to challenges after so much time has passed, particularly as duties for Indigenous consultation, participation and partnership have strengthened.

“There needs to be robust, iterative participation with our First Nations,” said Herron. He points out that modernising the accommodation arrangement and paying attention to the waters and the traditional territories of the Wolastoqey nations, as well as the Mi’kmaq, is part of this engagement.

“I believe that the highest form of accommodation is that of ownership,” he said. “And I would envision that – from a mining perspective – we would have equity participation with First Nations.”

Processing ambitions and limitations

Sisson’s feasibility study includes an on-site ammonium paratungstate (APT) plant designed to produce approximately 4,457 tonnes of contained tungsten annually. This matters because Canada does not have high-end processing capacity for tungsten.

If developed, Sisson would represent the first commercial APT processing facility in Canada. APT is a crucial intermediate product. It is more valuable and transportable than raw ore concentrate, and a tradeable commodity in global tungsten markets. Herron notes there is commitment for this initial processing in New Brunswick, with government pushing for “as much of this early-stage value-added work in situ as possible.”

But he acknowledges limitations as higher-value processing stages. Converting APT into tungsten carbide, alloys, and advanced products, will remain concentrated in China and select allied nations.

Timeline and Path Forward

Northcliff Resources, owners of the Sisson Project, is now aiming for a final investment decision “in the front of 2027,” with major construction beginning around mid-2027 and production starting by mid-2029, said Herron.

Currently, the company is focused on front-end engineering and design, he said, with issues related to their environmental EIA and the 40 outstanding conditions of the EIA.

Herron’s repeated emphasis on social licence reflects hard-learned lessons from New Brunswick’s mining history. The province appears to recognise that rushing development, cutting environmental corners, or inadequately addressing Indigenous concerns would damage prospects for the broader critical minerals sector it hopes to develop.

Whether mid-2029 production proves achievable depends entirely on navigating this social licence challenge while meeting technical, environmental, and regulatory requirements. In Herron’s framing, the timeline is secondary to getting the fundamentals right: “We need to be immensely responsible from an environmental perspective... if that’s not in place, you risk losing social licence.”

For a province attempting to position itself as a reliable Western tungsten supplier in an increasingly fraught geopolitical environment, the most strategic calculation may be Herron’s insistence that environmental responsibility and social license aren’t obstacles to overcome but foundations to build upon.

The question isn’t whether New Brunswick can develop Sisson, it’s whether Sisson can demonstrate that critical minerals development and environmental responsibility are compatible goals rather than competing priorities. Whether rhetoric becomes enforceable institutional reality will determine not just one mine’s fate, but the viability of New Brunswick’s broader ambition to return mining to economic relevance.

Support Local Reporting & Analysis

Want more deep dives like this? Becoming a paying supporter of Side Walks and follow our continuing coverage of the issues shaping Atlantic Canada’s future.

Keep the Conversation Going.

If these issues matter to you, help us amplify them and share this story with others who want to understand the world from an Atlantic perspective. Every share brings more voices into the discussion and strengthens independent reporting on Canada’s East Coast.

Excellent reporting on how dry stacking isn't the silver bullet environmentalists hoped for. The molybdenum complication shows how real-world geochemistry forces harder choices than policy debates usually acknowledge. I've seen similar tailings debates elsewhere where each solution just swaps one set of risks for another. Herron framing social license as a foundation rather than an obstacle seems smarter than usual political posturing, but enforecment will be the real test.

Let’s talk please We haven’t stopped mining 💡